I just completed a big art project, an installation for the PSVI Film Festival at the British Film Institute in London.

PSVI stands for ‘preventing sexual violence in conflict’ – that is, calling attention to the problem of rape used as a weapon of war. The PSVI FIlm Festival 2018 was part of a wider Foreign and Commonwealth Office* initiative to prevent and punish war-rape across the globe. The UK has been really proactive in this. The festival was a chance to publicise the work the FCO does. It was hosted by the film star and activist Angeline Jolie who has been hugely active in this area.

When was asked by the FCO to get involved – as producer of the event as well as installation artist – I confess I didn’t know much about the subject, it’s pretty much pushed under the rug. I was aware of the historical court case where Bosnian women successfully prosecuted the Milosevic regime for war rape and in doing so, made war rape a war crime. I wasn’t aware though of the ongoing trauma and stigma attached to the survivors, the children born of war rape and – even more awful, if that is possible – the continuation of these atrocious attacks on civilian populations, especially in the violence of Syria and Congo in particular.

So, how to make art that addresses that? I quailed.

Not only that. I was asked to create an art installation to fill the entire ROOM – a huge foyer at the British FIlm Institute building in London’s South Bank Centre. Something that would fill the vertical space, which is massive. I quailed even more.

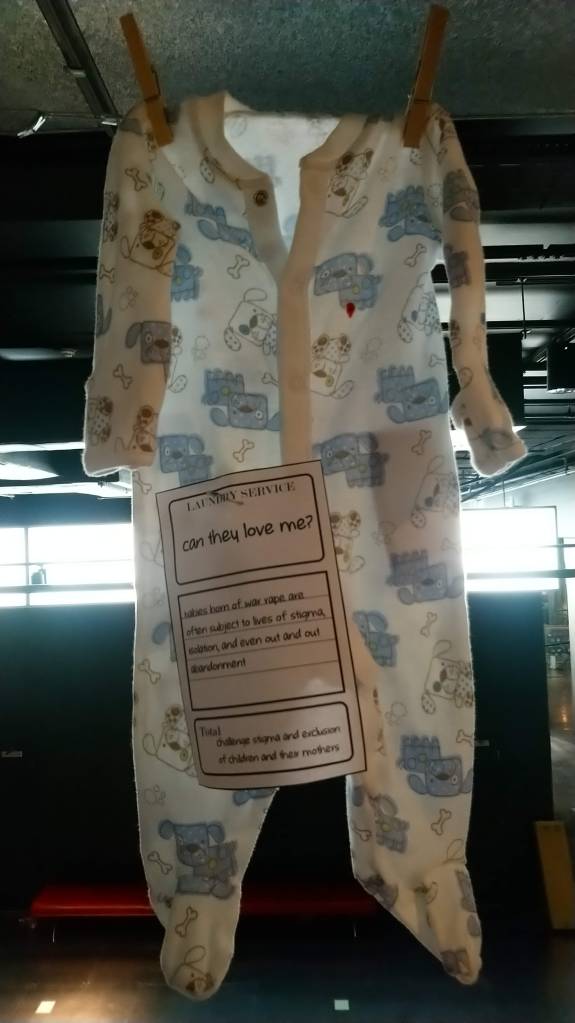

After considering a variety of approaches to fill the large foyer and mezzanine areas of the BFI, I wanted to take an unusual approach to installation. I decided to create washing lines across the ceiling to ‘air out the laundry’ – that is, to bring out that which is normally intimate and hidden.

I wanted to include graphic drawing, which is rarely seen on a large scale and even more rarely as [art of installation. Now, I don’t really draw and definitely don’t do it well so I called upon a young artist whose work I’ve been following for a few years, Anna Chiarini. The idea was to ask Anna to do one or two drawings on large sheets, and include the within a collection of clothes and texts.

However when I saw the way Anna grasped the idea and the drawings she rapidly produced – many inspired by a visit to the Calais border a few years ago – I rethought the installation and began to build it around the drawings, instead of simply including one or two.

I was also responsible for programming and scheduling the Film Festival so I was able to preview most of the films that we were going to screen. By doing this together Anna and I were able to get a very clear idea of what the whole festival is about, which guided us in designing and creating the installation. As harrowing as as it was to watch the films it was a real education and it helped us to understand how we could sense sensitively but evocatively create an artwork that would bring home how important the subject is – but also inspire action through art.

Of course we were never going to depict the experience of rape. We were moved by the lives of survivors, the initiatives which are being rolled out by the UK Foreign Office and NGOs , and the work that survivors are doing for themselves. We wanted to also call attention to how much more work needs to be done, especially in bringing an end to stigma against survivors and their children. And finally to honour Dr Denis Mukwege and Nadia Murad, joint winners of the Nobel Peace Prize 2018 for their work on PSVI.

It was a difficult project, emotionally difficult and tactically not easy, but I feel that it was a privilege to have been able to contribute.

*The FCO is now known as the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, or FCOD

The films shown at the festival are listed here

A review of the festival by Janine Natalya Clark

The Importance of Enabling Movement: Some Reflections from the PSVI Film Festival CSRS

Principal Investigator – Professor Janine Natalya Clark – writes for the project’s “Stories from the Field” blog.

Published 10 December 2018

During the recent PSVI Film Festival in London, I watched several films about conflict-related sexual violence, including Libya: Unspeakable Crime (2018). This documentary film primarily focuses on male victims/survivors, who rarely come forward to seek help. We are told that when a Libyan man suffers sexual violence, local people will ask ‘What did he do to deserve it?’ Graphic details are given about some of the extreme abuses and depravities that men have been forced to endure in Libyan prisons and other places of detention. The men’s faces are not shown, and in many ways this makes the film more powerful. One wonders about the men’s eyes and the emotions that they express. In one part of the film, a man enters the room. He has a walking stick and sits down slowly. The camera pans to the lower part of his face, to his beard which is flecked with hints of grey. He looks to be in his mid-fifties at least. We are told that he is just 27 years old. I think about the possible injuries that he may have suffered; untreated injuries that he is too afraid or ashamed to reveal. His body looks worn and haggard. It moves with difficulty. In the film Breaking the Silence – Sexual Violence under the Khmer Rouge (2017), a different type of movement catches my attention. As Cambodia deals with the legacy of Pol Pot’s Democratic Kampuchea, there has been significant emphasis on artistic projects. One of these is a classical dance drama (called Phka Sla) about forced marriage during the Khmer Rouge regime. The dancers move with ease and grace, using their bodies to tell a story and to inform younger generations about the past. Phka Sla moves audiences in an emotional sense. According to John Shapiro, the executive director of the Khmer Arts Academy, ‘Empathy is one of the most important things you can share with and develop in any population’. The film that had the biggest impact on me was City of Joy (2016). Established in 2011, the City of Joy – based in Bukavu in the Democratic Republic of Congo – provides women who have suffered conflict-related sexual violence with new skills, it informs them about their rights and it seeks to empower them to become leaders. The City of Joy’s fundamental aim is to transform pain into power. I never imagined that I would laugh whilst watching a documentary film about conflict-related sexual violence. At one point in the film, Eve Ensler – author of the Vagina Monologues – asks all of the women to lie on the floor, each one with her head on another woman’s stomach. When the women feel the stomach under them moving with laughter, they too have to laugh. The writhing mass of bodies conveys a sense of solidarity, joy and movement. Despite everything that they have gone through, the women are rebuilding their lives and helping each other to go forward. The City of Joy is an inspiring film. I left the auditorium feeling uplifted and intrigued about the possibility of creating Cities of Joy in other countries. This is something that the human rights activist and City of Joy director, Christine Schuler Deschryver, would ultimately like to do. But then I think about some of our CSRS research participants in Uganda. Some of them are living with intense pain, from bullets lodged in their bodies and unhealed physical wounds. Their movements are slow and laboured, like the man in the Libyan film. The women at the City of Joy have received treatment from the Panzi Hospital and this year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner, the Congolese gynaecologist Dr Denis Mukwege. This has helped them to transform their pain into power. Such transformation, however, will always be extremely difficult if survivors struggle to move comfortably in their own bodies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.