The New Media Gallery New Westminster Canada, February 18 – May 5, 2024

I was lucky enough to make a short trip to British Columbia in March, where I caught a fantastic exhibition at my favourite Canadian gallery, the New Media Gallery, situated just outside Vancouver in New Westminster. I’ve written about this gallery before, too. In my mind, it is undoubtedly the most exciting gallery in Western Canada. Regarding the kind of shows they put on and the whole approach to curation, it is probably my favourite gallery in Canada – although I admit that I’m probably missing more than a few.

ZOOVEILLANCE is the current exhibition’s title, which exemplifies the contradiction of contemporary technological advancement through the mediated observation of animal activity. Artists Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Mat Collishaw, and Marco Barotti have developed their contributions to the show. All are based on rigorous scientific, aesthetic and technological research. The artworks address our collective concerns about two powerful, hyper-transformative technologies: AI and Social Media . These emerged of at the tail end of in the 20th century and have been huge disruptors, and now dominate our present condition.

Marco Barotti’s APES starts with his observation of the WI-FI sector antennas, devices that are usually installed on rooftops in our cities. We don’t normally notice them, but they can be seen from above and photographed by drone. Barotti notices that seen from a certain angle, each resembles a primate clinging to a tree. He then takes this imaginative observation and – using discarded/recycled WI-FI sector antennas – builds the installation. The apes are continually climbing, shaking the trees as if trying to shake down coconuts or other food. We recognise their primal gesture and relate to it. But

“Apes are our closest relatives and are commonly seen as a symbol of our evolution” Marco Barotti

True, we have come a long way in a short time in creating smart systems that can think and—potentially—help us build a better future. But are we ready as a society to work as smartly as the machines we can make? Can the new digital evolution help us treat each other, the earth, and other species with more respect and for long-term sustainability? Or are we just fuelled by clicking and immediate gratification?

Balotti uses the Apes as a metaphor to show how our digital lives have changed. APES talks about cybersecurity, data usage, surveillance capitalism, fake news, changing people’s behaviour, and energy consumption. We are immediately invited to confront the pros and cons of the digital changes that are happening all around us. If we keep accelerating, won’t faster speeds and more data just make us consume more material things? How can we make sure that we don’t just make the world’s environmental problem worse? How can we make our society more cyber-resilient? How can I be more than just a monkey in a tree, trying to shake down the coconuts? How can I be a responsible member of the digital society>

Exhibition text:

The sculptures are driven by algorithms showing dynamic counters of data consumption and cyberattacks: from Facebook likes, Google searches, tinder swipes, internet energy consumed and emails sent to the adverse cyber events happening in real time. The data is analyzed and translated into sound. Based on the idea of surveillance Capitalism and behavioural modification through data appropriation, the APES are programmed to move with predictive patterns dictated by the various names appearing on the screens. These motions are accompanied by an evolving soundscape generated by a granular synthesizer driven by the data flows. When they counters hit certain key numbers, the sculptures release sonic events composed by an AI trained to deep fake the calls of real apes. These sonic events are modulated in real-time by the data speed and diffused as a quadraphonic audio experience using the body of the APES as a resonating chamber.

Marco Barotti, The New Media Gallery

Reconstructed Rhino

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s piece The Substitute was the most poignant work in the show, and perhaps I spent longer with it than the others. I will not lie: it broke my heart.

“On March 20, 2018, headlines announced the death of Sudan, the last male northern white rhinoceros. We briefly mourned a subspecies lost to human desire for the imagined life-enhancing properties of its horn, comforted that it might be brought back using biotechnology, albeit gestated by a different subspecies. But would humans protect a resurrected rhino, having decimated an entire species? And would this new rhino be real?”

Good questions, all. Ginsberg studied the case of Sudan and the efforts made to resurrect him and re-establish the northern white rhino.

(Attempts are now being made to fertilise eggs from the two surviving female white rhinos with sperm from Sudan in a lab and then put the resulting blastocysts into suitable female southern white rhinos. There are now eggs from two females and sperm from five males that could be used to bring the species back to life. The team in charge made three eggs in 2019; they are being kept in a lab right now. They plan to put the embryos into southern white rhinos to carry the pregnancy since the two surviving female northern white rhinoceroses are not healthy enough to do so.)

‘500 years ago, the first rhino in modern times was brought to Europe as modern science emerged, and now scientists hope to bring back a rhino using sperm cells created from skin cells from a now-dead rhino.

Why do modern western societies value new technology and new forms of life such as synthetic biology or artificial intelligence (AI) more than the fragile life that already exists around us? Why do we invest in innovation and the new rather than in protecting the natural environment that enables our existence?’ Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg

Ginsberg’s “The Substitute” addresses the paradox of how we care so much about making new life forms while ignoring the ones we already have. A northern white rhino is digitally “brought back to life” in the piece, presented as a life-sized projection. Based on research from AI lab DeepMind, the rhino acts like an artificial agent, which means it can learn from its surroundings on its own. The faux rhino roams in a virtual world, becoming more “real” as it learns the limits of the place it inhabits. Over time, the rhino is ‘born’ out of a mass of pixels, strides across the screen and becomes ever more uncannily real. Until it vanishes. The moment of vanishing is terrible and devastating. It brings home the death of Sudan and all the other species we have wiped out. The mass of pixels appears again, and gradually, a new rhino is ‘born. But by now, we know how false it is and what we have done.

This is a perfect example of art that is tremendously upsetting and starkly necessary.

Promise Box

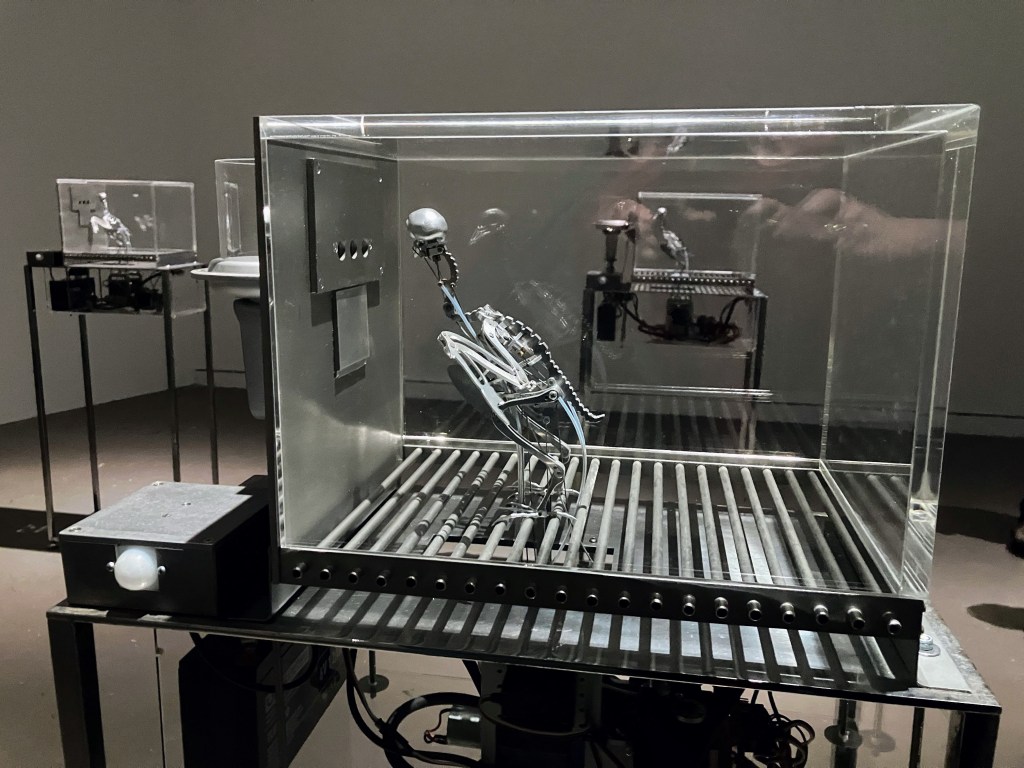

The historic behavioural experiments of American psychologist B.F Skinner inspire Matt Collishaw’s Machine Zone. Skinner explored the idea of random reward and operant conditioning (conditioning the agent to actively choose to do something, rather than to passively react to a stimulus).

I remember studying Psychology as an undergraduate (it wasn’t my major, but I studied it for three years). I was absolutely struck with horror at what Skinner and the other behavioural psychologists had done. I remember in one lecture vehemently objecting to having to study some of the research that John Watson and Skinner did on animals and children. It was absolutely horrendous; basically, they were vivisectionists of the worst kind. I was fortunate because I was later able to study Jungian psychology with a wonderful teacher who had trained at the Jung Institute, and I never got over my horror at behavioural psychology. I digress.

Anyway, I had actually forgotten about Skinner until I walked into Collishaw’s impressive and aesthetically beguiling installation. The room was filled with “Skinner Boxes” rendered as small silver bird cages where exquisite mechanical birds perched, spread their wings and generally behaved in a birdlike manner. I was captivated, reminded of the beautiful mechanical birds of the 18th century, the jewelled automata. At varying times the cages holding Collishaw’s birds would open up a small drawer and the bird would peck at it. The curator, Sarah Joyce, explained to us viewers that the birds in the real experiment were subjected to random rewards, and got addicted to the anticipation of reward.

Joyce then explained that Collishaw was aware that the algorithms that power social media interactions extensively use Skinner’s work on random reward. I did not know that, and it horrifies me because it exploits a our ingrained psychological weaknesses and susceptibility to conditioning. As shown in Skinner’s operant conditioning boxes, random rewards condition a behavioural loop by exploiting our natural motivations, creating a state of continual uncertainty. Nasty.

‘Skinner’s ghost has persisted into the modern day, a quiet spectre among our statuses, likes, comments, and shares’. Matt Collishaw

Another powerful, worthwhile exhibition that has haunted me since I saw it. It’s on til May 5, with an online talk by Matt Collishaw on May 3 which I’ll be attending. https://newmediagallery.ca/

https://www.instagram.com/daisyginsberg/

The New Media Gallery is on Columbia St New Westminster next to New Westminster Skytrain. The best places to eat are the beautiful and elegant Piva Restaurant on the Anvil ground floor, or Hyack Sushi about a block away up 8th St.

You must be logged in to post a comment.