Saferkhan Gallery in Zamalek is showing a collection of work by the 20thC artist

What made a young francophone girl from Egypt’s elite, privileged class decide to turn her back on all of that and become an artist? To spend her family wealth on supporting Cairo’s Surrealist Group? To become an active Communist and spend years in prison? All the while painting and drawing evocative works that reflect her most urgent concerns: her own frustration and despair, her fascinating observations of place and people, and her formal explorations of light and colour in Egypt’s landscape.

Actualy history is full of dissatisfied elites who rebelled against privilege. Che Guevara is one. But not many of them became important artists. Natalia Goncharova is an example of one. But she fled revolutionary Russia and spent her life in Paris. Inji Afflatoun was committed to Egypt, to identifying as an Egyptian and was willing to pay the price.

It’s impossible to give a full description of Afflatoun’s work: she lived long and had different phases, and there’s no definitive book on her life or work, though she did publish a memoir (sadly unavailable in English translation). One book that gives a decent account of her in her Surrealist period is Surrealism in Egypt: Modernism and the Art and Liberty Group by Sam Bardaouil and his book accompanying the exhibition Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism. But for the most part, to find out more about her I have relied on collecting various news articles and academic papers.

A good overview can be found here at the Saferkhan Gallery’s website.

“I, who speak French, have wasted eighteen years of my life in this cellophane-wrapped society. Until the age of 17 my language was French and even when I started dealing with the people I couldn’t get rid of this complex,” Inji wrote.

She grew up speaking only French, and had to learn Arabic as a young adult. Many of her contemporaries would never have bothered. But creativity ran in her veins; her mother set herself up as a fashion designer and bespoke fashion house after her divorce, and though Inji’s upbringing was privileged she already had the example of a strong-minded, creative woman in her life. Clearly there could be more to life.

In one painting from her early 20s The Girl and the Beast, 1941 she paints roiling rough waters and a bleak landscape. A barren tree bent by the wind stands on a distant shore, and upon a rocky outcrop, thorny bushes and small uninviting plants manage to grow. A woman in a ragged blue dress is caught up in the bush, fighting to get free. Worse, a huge sharp-beaked bird-beast with claws is flying her way. It is nightmare image straight out of the surrealist playbook – as disturbing and sincere as Dorothea Tanning’s haunting Ein Kleine Nachtmusik or any of Leonora Carrington’s pictures. I’d love to see this and Inji’s other paintings from that era included in the history of Surrealist Women. As it has, I think, become appreciated, surrealism was different for women. They had to battle the entrenched misogyny and even fetishism of the male Surrealists (Andre Breton and Salvador Dali are just the two most notorious) as well as work out and devise their own surrealist practice AND endure the restrictions on women in general in that period.

But Inji is not defined by surrealism. Her decision to venture forth out of the capital and away from the European-influenced Egypt that she knew well, into the rural world changed her as a painter. Her pictures from this time remind me of Diego Rivera‘s depictions of rural Mexico: generous, unintrusive, respectful, detailed, humanizing. Rivera and Afflatoun had in common their adoption of Communist principles. This was not unusual among artists, especially Surrealists. Today it seems odd that talented artists like Afflatoun, Rivera, Frida Kahlo, and Tina Modotti – to name a few – would give themselves over to Communism, even to the point of accepting Stalin. But in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, it really looked like Communism offered the best opportunity for hope and improvement in the lives of the majority of people. Many of Stalin’s worst atrocities were hidden. And it was different for these artists than it was for Europeans. While European artists like Breton could flee fascism for America and Britain, for example, people from colonized countries like Egypt did not feel the same way about the colonizing nations. And let’s not forget racism. While aristocrats like Inji would not have been lumped in with the Egyptian masses, dismissed by many as ‘brown people’ she was no doubt aware of how Egyptian natives were treated by the occupying British. Communism offered something different – though I think we all know by now that they never really delivered.

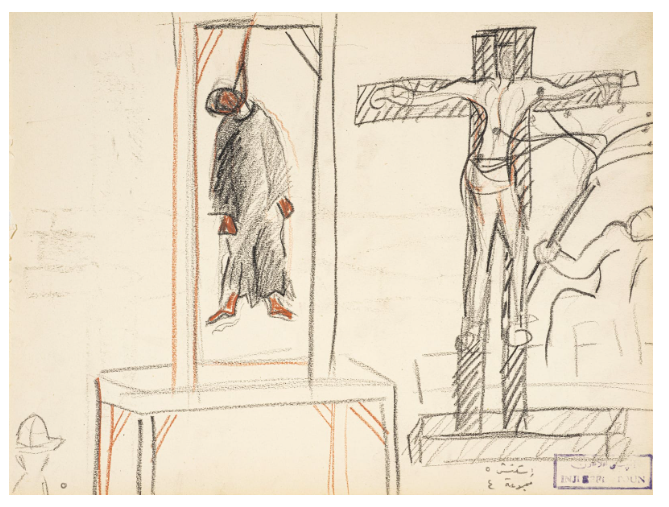

pencil on paper

Afflatoun’s views on colonialism are expressed well by some drawings in the Saferkhan exhibition. These small pieces are imagined renderings of the executions of the Dinshaway Incident. The Dinshaway Incident, sometimes called the DInshaway Massacre, was a confrontation in 1906 between residents of the Egyptian village of Dinshaway and British officers during the occupation of Egypt (1882–1952). * Inji draws the plight of each individual villager with precision and empathy, without sensationalizing the subject. These are simple yet powerful.

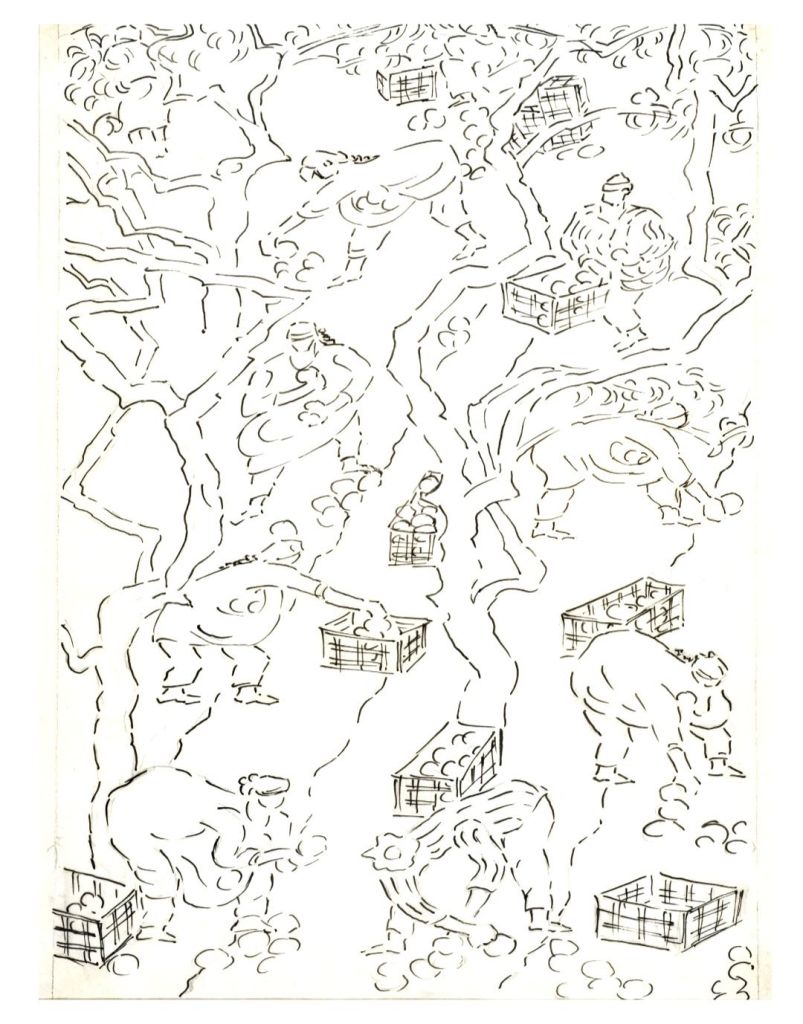

Many of the works in the Remembering Inji exhibition are drawings and sketches, in coloured pencil or simple ink. These give a different perspective to her paintings which you can see in the Museum of Modern Egyptian Art. Simple depcitions of villagers gathering fruit in an orchard are treated to an unusual perspective, rendering the picture almost abstract.

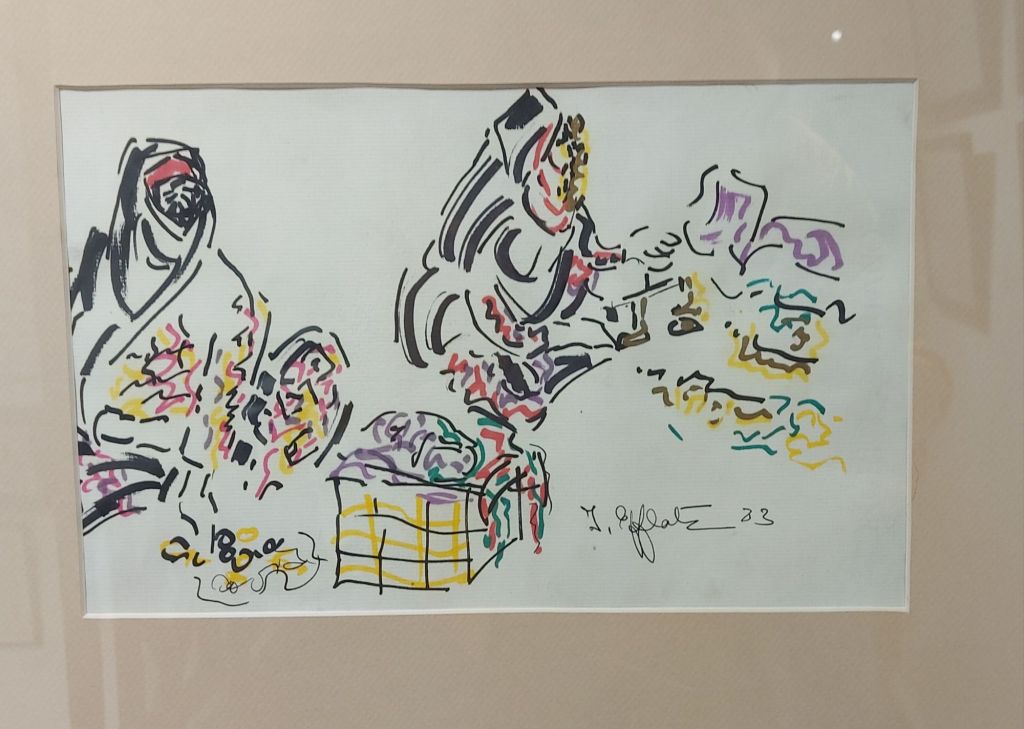

In other drawings, coloured pencil captures quickly the shimmering diffused light and shifting colours of Egypt in summer.

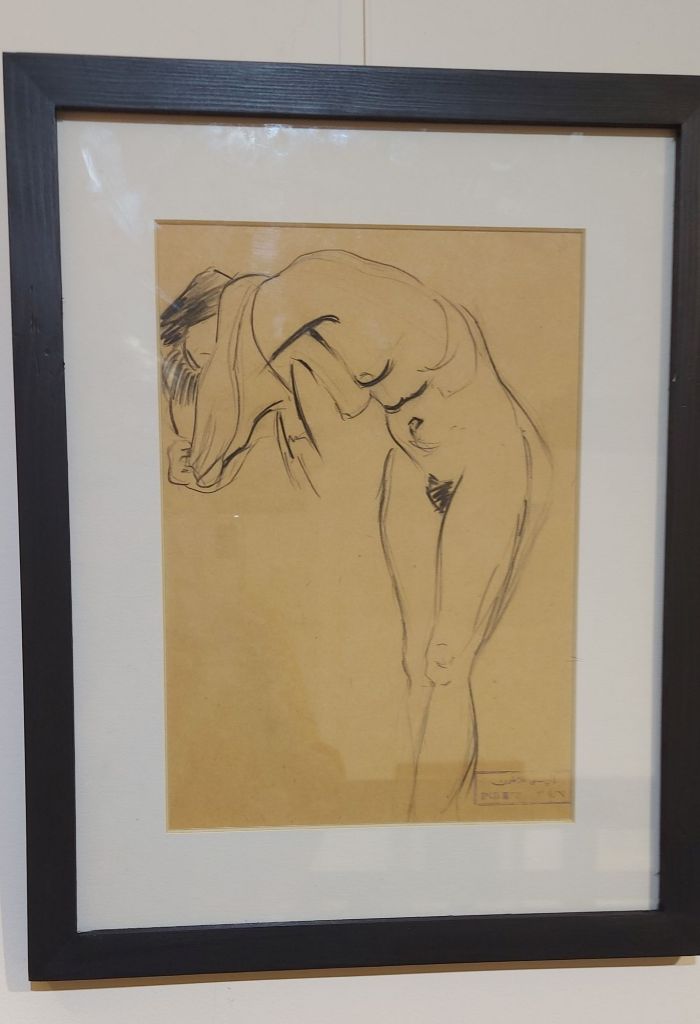

Finally, my favourite of the drawings, a small simple female nude.

It’s always interesting to see a female nude made by a woman artist compared to one made by a man. There are unsurprisingly few nudes by women compared to those by men. Inji’s Undressing Nude is a figure in motion. Not in repose. She is seen, but is unaware of or uninterested in the viewer. Her body is taut, in the act of removing clothing but shes not acting sexy or performing for a lover or a viewer. Yet her sex is bare, full frontal. It isn’t coyly hidden. It’s brazen and hairy and strong. The breasts sag with the posture. It’s such a natural, gorgeous evocation of the human body!

If you’re in Cairo – go and see the show in Zamalek, then head down to the Modern Art Museum to see the paintings.

If you’re not in Cairo, check out Safarkhan’s website. https://www.safarkhan.com/exhibitions/35/works/

Safarkhan Gallery is in Zamakek. There are plenty of nearby galleries to see in the neighbourhood; I recommend also visiting Picasso Gallery. Both spaces are small and always worth stopping by. The island has a limitless range of great cafes and restaurants nearby. Last time I visited I went to Cafe 30 North, at 16 Mohammed Thakeb, Abu Al Feda, Zamalek.

- The peace of Dinshaway was disrupted when British officers, in pursuit of sport, hunted the pigeons that were crucial to the locals’ livelihood. A confrontation ensued, leading to the accidental firing of a gun by an officer, injuring a female villager and inciting further hostility towards the soldiers. One officer, attempting to flee the escalating situation, succumbed to the oppressive midday heat and perished outside the British camp, likely due to heatstroke. When a villager found the officer and tried to help, he was misconstrued by other soldiers as the perpetrator of the officer’s demise and was consequently killed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.