Citra Sasmita’s London exhibition exploring Balinese mythology and women’s roles at Barbican Curve Gallery, London

Enter into the vibrant world of Balinese art as Citra Sasmita’s groundbreaking UK exhibition unfolds. This unique show at Barbican Curve blends traditional mythology and powerful narratives of women through captivating paintings and installations. Discover how Sasmita reimagines ancient forms like Kamaasan painting with a contemporary lens, offering a profound exploration of culture and rebirth.

Into Eternal Land, the first solo exhibition of Balinese artist Citra Sasmita in the UK, combines elements of folk art (collaborating with women folk artists) and fine art installation with a reconfiguration of traditional mythology, aiming to take the audience on a symbolic journey through ancestral memory, ritual, and iconography. The Indonesian archipelago has a long history of displacement and migration, and Sasmita draws inspiration from a broad and diverse range of sources, including local mythologies from Bali and Indonesia, the great Hindu epic Mahabharata, and Dante’s Inferno. Citra Sasmita, a self-taught artist, has been receiving deserved attention of the past few years and it’s wonderful the Barbican has made it possible for us to view a comprehensive show of her work.

The exhibition has several parts, and the Barbican’s Curve gallery is an ideal place to see the work at its best because of its superb acoustics. The musical compositions by Agha Praditya Yogaswara can be heard with an appropriate, clean tonality.

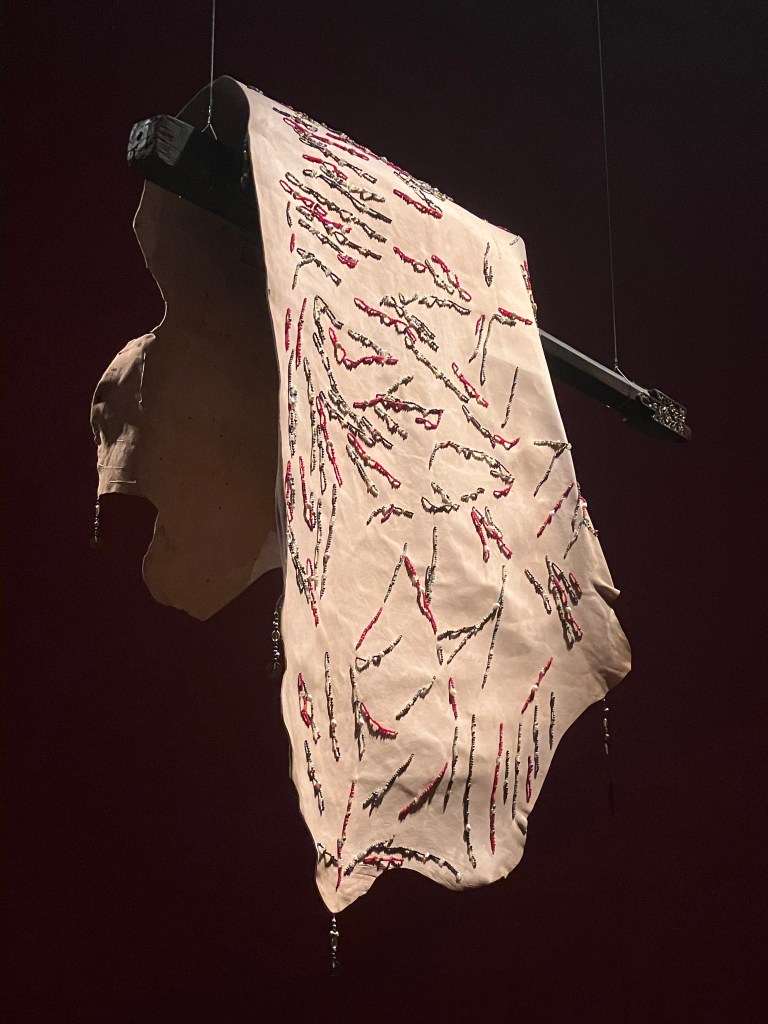

The Curve also offers the opportunity to move through Sasmita’s work and appreciate each craft and type of material she’s working with.. At the start of the exhibition, we see beads embroidered onto hides, which I’m assuming is some tradition, although, to be honest, I don’t know enough about Bali to say.. But I notice the hides hang on magnificent carved antique wooden pillars. This is a piece called Prologue,, and it is indeed the prologue to the show..

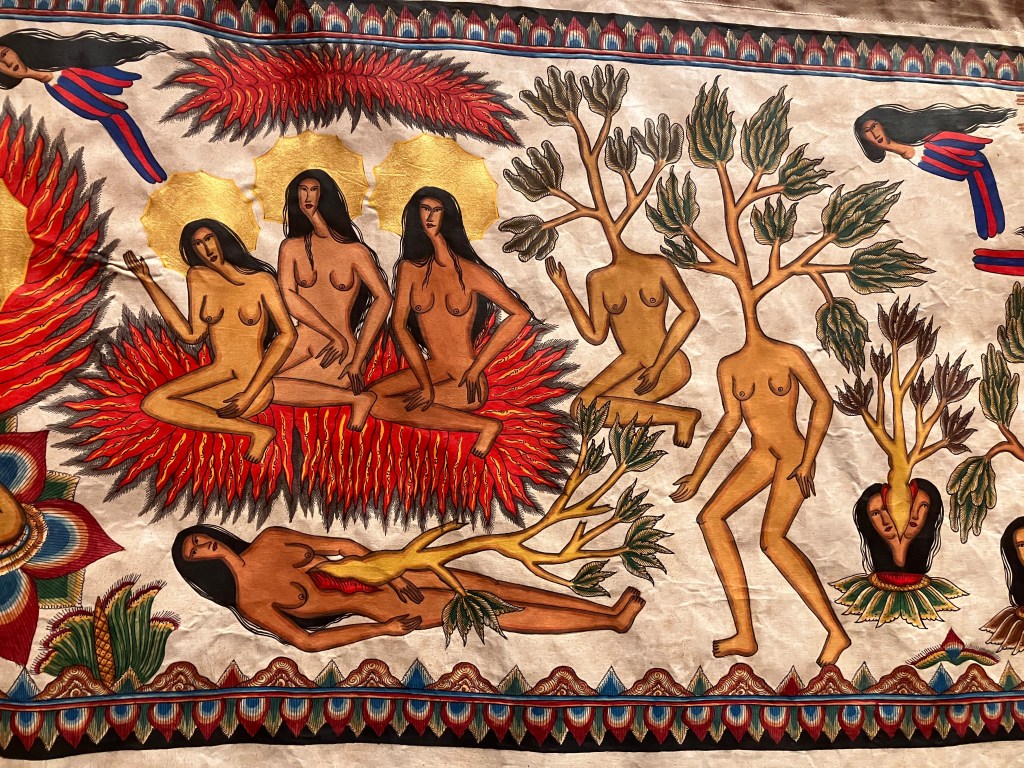

Moving through, the second work comprises four large horizontal frieze-like Kamasan paintings.

Kamasan is a specifically Balinese form of painting.

Kamasan painting is a traditional Balinese art form originating from the Kamasan village near Klungkung in East Bali. It is known for its unique style, which often depicts scenes from the Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. The paintings are characterised by their detailed lines, vibrant colours (usually red and ochre), and natural pigments derived from local plants and minerals. Stylised figures are characteristic of the approach. Kamasan paintings are not just works of art but also have a profound cultural and religious significance. They are often used in temples, palaces, and ritual practices. While the tradition is deeply rooted in the past, Kamasan painting has also adapted to modern times with commercialisation and contemporary art pieces created in the village.

Sasmita has involved a Kamasan painter, Ni Wayan Sukhartini, to do the paintings. The artist uses acrylic paint instead of traditional pigments. I don’t know how this might affect the outcome, as I can only see examples of Kamasan online. The style is completely different from the Balinese tradition. I would love to know more about the ways that Ni Wayan Sukhartini created the images with Sasmita.

The images seemed on the surface a bit disturbing (OK, to be honest, they are rather horrific), but they are meant to be revelations of women undergoing transformation and rebirth

According to the exhibition text, Sasmita’s practise challenges traditional narratives and rejects formerly dominant Dutch colonial conceptions of Bali. She reinvents the motifs and materials of Kamasan painting which dates from the 15th century and was historically produced exclusively by men. Apparently in the traditional paintings women were either sexualized, depicted solely as child-bearers or cast as evil. Sasmita’s interpretation depicts powerful women exhibiting a raw yet post-patriarchal sexuality.

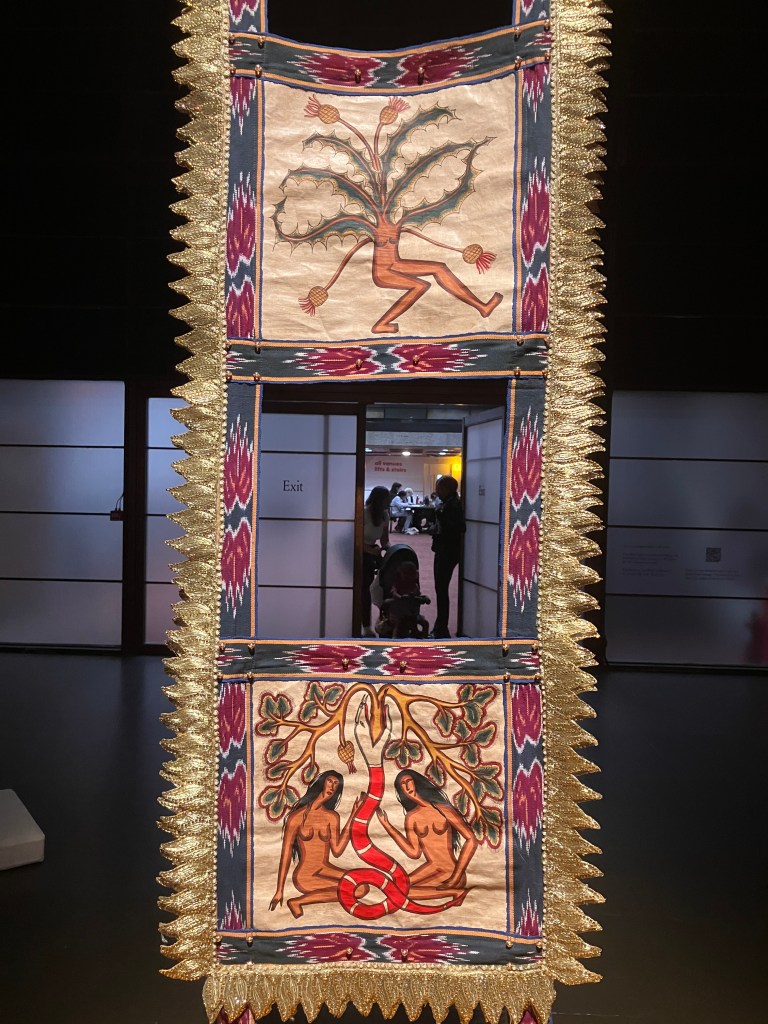

Passing the Kamasan paintings, we encounter two huge vertical installations where striking vertical paintings in the same style as the Kamasans are applied directly to the skin of a python.. I was quite astonished to see the python skin and wasn’t sure if it was real, but the gallery assistant confirmed to me that it was. I am strongly averse to using animal parts in art, and while I was really impressed with the work, it still couldn’t help but disgust me. This appears to be the skin of the reticulated python, given its huge size; it is the largest snake native to Asia. These pythons are commercially exploited for their skins, meat, and medicine and are harvested by rural people in the country. There’s evidence that Indonesian pythons have been commercially used for over 100 years without significant population declines. The inclusion of the serpent skin makes sense in the context of the reiterated symbol of the snake throughout the exhibition (see below on the significance of the serpent in Balinese folk culture). Still, I wish she had not used the Python’s skin in her art.

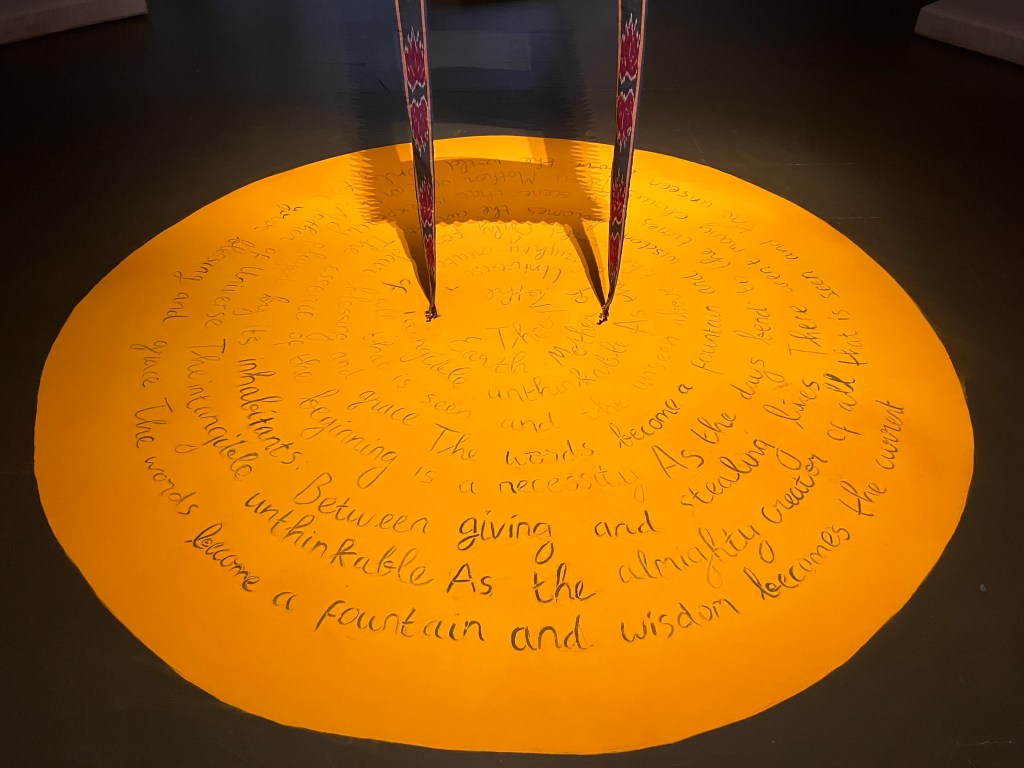

In the next work we move away from painting into stitchwork; Jero Mangku Istri Runi created the embroidery. These panels are particularly striking to my mind, more appealing than the Kamasan paintings, simply because of the sheer pleasure in looking at the stitchwork At the end of the exhibition, there is a large multipart embroidery piece like a ladder reaching up to the top of the ceiling but grounded in a striking mound of real turmeric spice, in which the artist has written a prayer.

Sasmita’s collaboration with traditional folk artists is truly confident and expertly executed. Looking at the work in this exhibition and the online pictures of the traditional work, it’s evident how Sasmita has adapted the symbolism and images. It would have been fascinating to witness this collaboration in action. I would have loved to see documentation of the artists working together; it would have been a real asset to the exhibition. The clear skill and understanding of the tradition coming from the folk artists blends seamlessly with the artist’s vision, and I believe this combination works exceptionally well. In this show, filled with wild women, frenetic rituals, and the merging of nature forms such as trees and snakes with humans, Sasmita demonstrates her interest in exploring the problematic histories of Balinese culture and colonial interpretations.

On her website Sasmita describes her work as ‘imagining a secular and empowered mythology for a post-patriarchal future’ which is a summing up I certainly agree with.

Serpents in Balinese folk culture

After seeing the show, I needed to look up the significance of the serpent in Balinese folk culture, as I could not bear to respond to the snakes with my own default Judeo-Christian interpretation.

In Balinese folk culture, serpents, particularly snakes and the mythical Naga (dragon-serpent), hold a significant spiritual and symbolic role. They are often associated with power, balance, protection, and connection to the divine. Snakes are seen as guardians of sacred places, like the Pura Tanah Lot temple, and are also believed to embody the forces of Kundalini, a spiritual energy. The mythical Naga, often depicted in temple carvings, represents the cosmic balance between good and evil. In the Balinese creation myth, the world serpent, Antaboga, is the primordial being who existed before the creation of the world. The King Cobra is seen as a sacred animal, and encountering one during a ceremony is believed to signify a bountiful harvest and protection from natural disaster. Sea snakes, like the Banded Sea Krait, are considered sacred.

You must be logged in to post a comment.