Contemporary Art Transforms Riba-roja de Túria’s multilayered Visigoth era castle hosts stunning contemporary art

Arriving at the very last stop on the Valencia Metro at Riba-roja de Túria was like being transported back in time. This little town lies on the banks of the river Turia, the part that is still a river, not the part that has been diverted. Valencia was home to generations of Iberians, Romans, Visigoths and Muslims; they all settled here, and all of them left marks of their time, which you can see here in this microcosmic little town.

The Visigoth Castle is a prominent landmark in Riba-roja de Túria. It houses the Pla de Nadal museum and serves as a contemporary art centre.

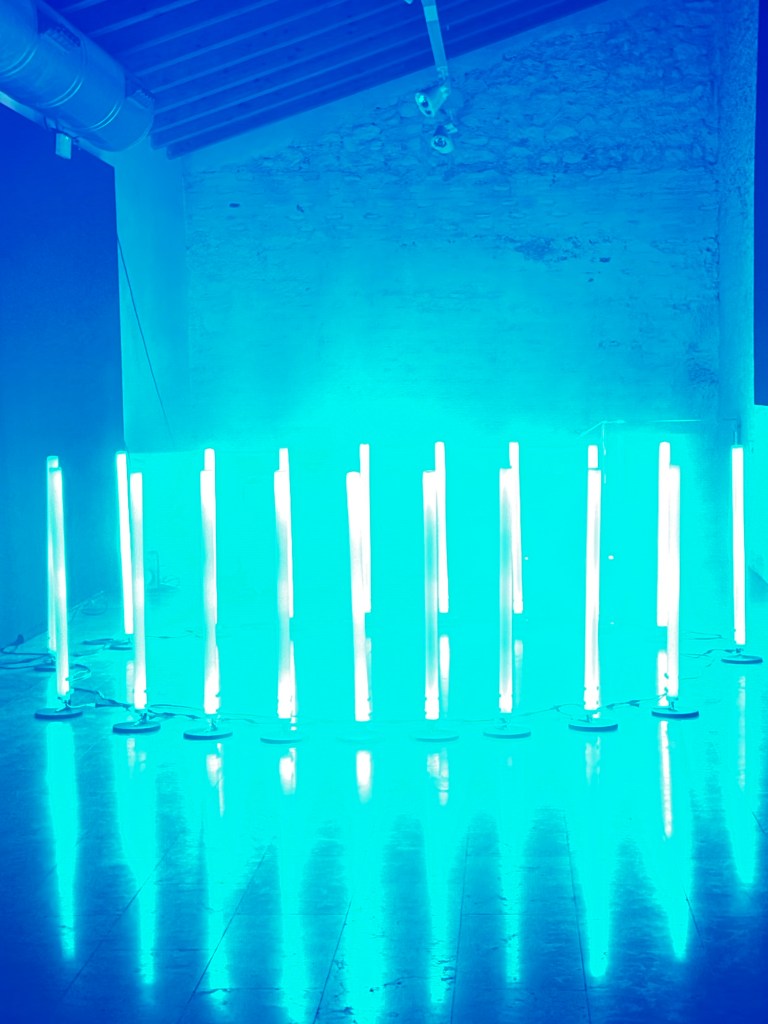

Int3raccion3s is a multidisciplinary project of the Cisma group, that investigates contemporary modes of interaction between art, technology, and society. It features 19 works by more than 20 artists, combining established trajectories and emerging practices.

It displays multimedia installations, performance, video art, generative artificial intelligence, laser installations, fibre optics, video game development, and creation labs. The works begin with wild experimentation and employ technology as a tool for thought, production, and encounter.

Int3raccion3s encourages new types of relationships, artistic research in digital and hybrid environments, and interdisciplinary collaboration. The historic environs of the Riba-roja Castle thus become a space for experimentation, learning, and shared experience, with interaction serving as a catalyst for knowledge and transformation.

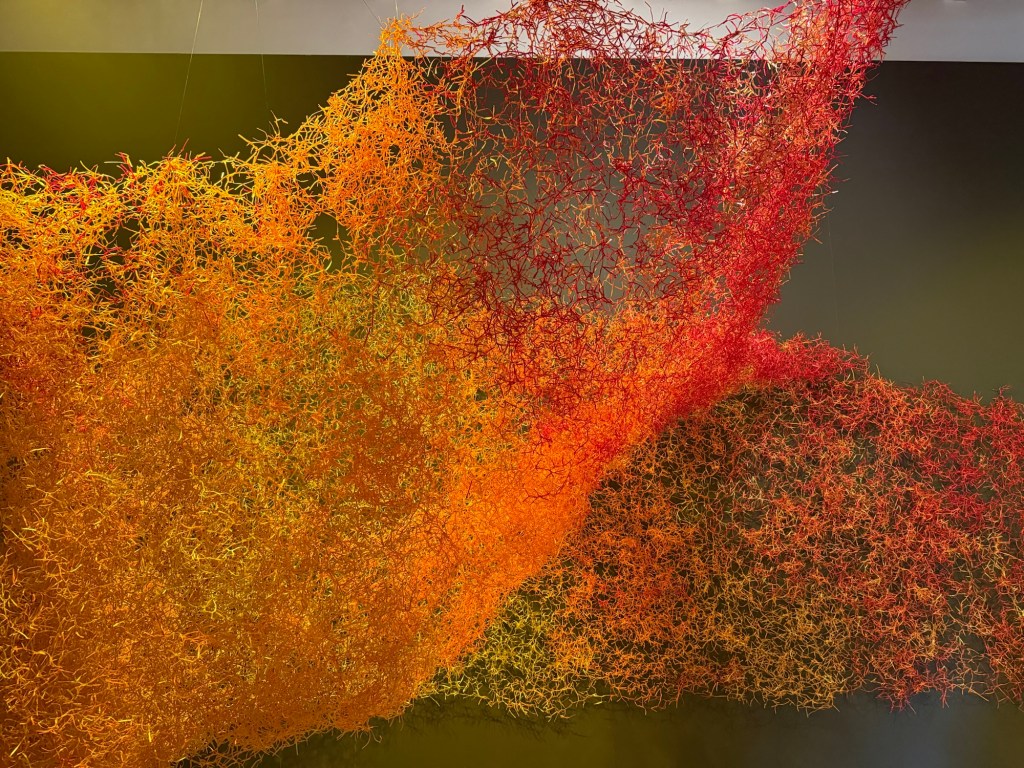

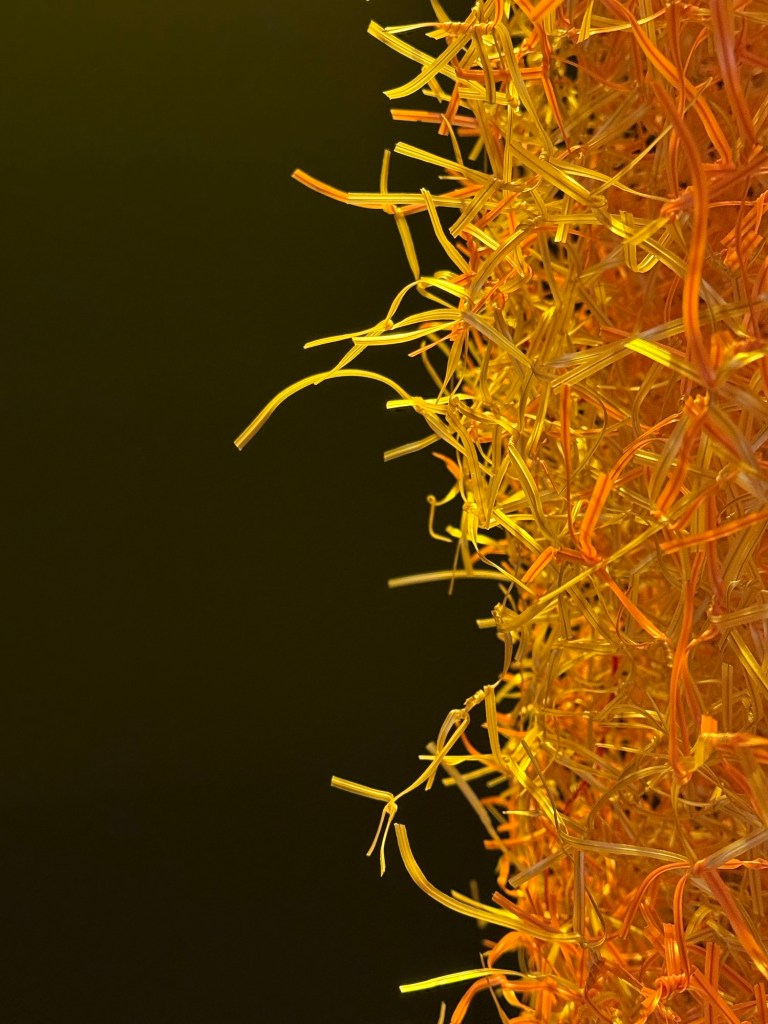

Claudia Martinez’s marvellous “Desborde” is a huge, expansive woven mass made of shreds of orange plastic with a wire core in red, orange, and gold. The structure, made of approximately 100,000 metres of wire and 3 million knots, expresses the fractal concept, a knot that repeats itself infinitely and connects the various parts of the mesh with a wide range of permutations.

There is no narration or forced meaning to the piece beyond being what it is. Situated on the border between sculpture and drawing, embroidery and basketry, the work recalls many of the craft traditions of the region while at the same time exploring the deepest and most philosophical questions about the nature of matter and existence. Despite its appearance as if emanating from the cosmos, it is handcrafted. We can only imagine the hours expended, and the many hands working to spin quickly, forming knots and twists that will become part of a this magnificent whole.

This is the second time I have seen this work: I saw it at about two weeks before at a preview and I stood in front of it gobsmacked and allured. clearly, I could see it many more times and still feel the visceral thrill of it..

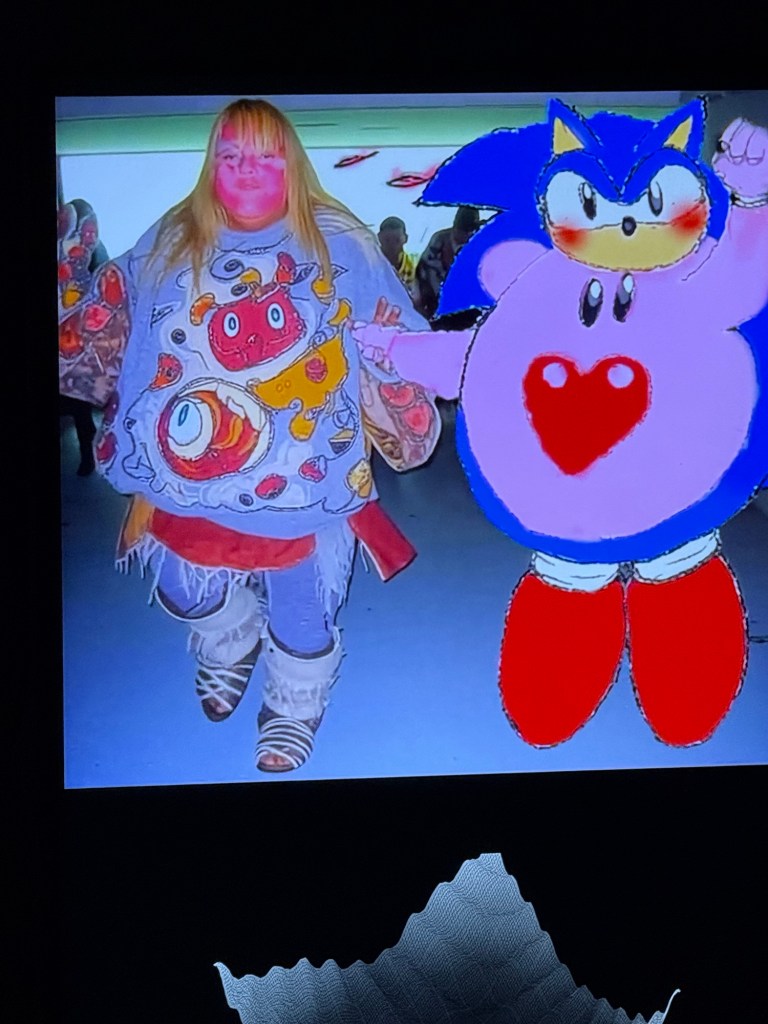

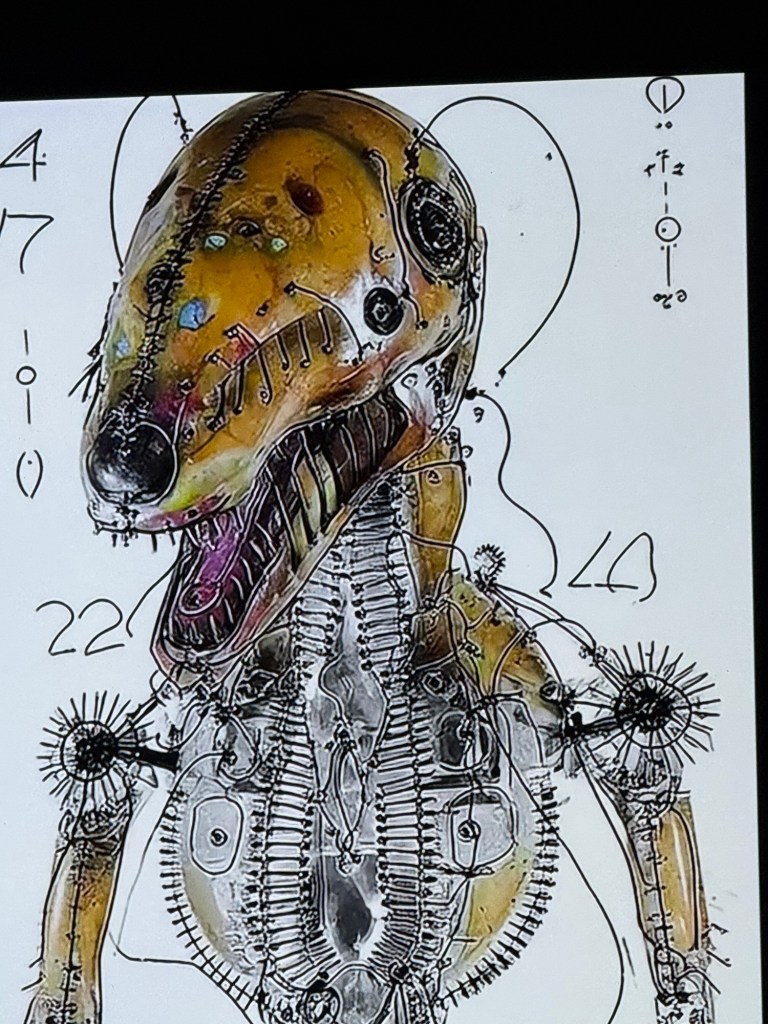

I love Elena Perez’s Remembering Orion because it feels like watching an intelligence outside myself help me to imagine. It is not simply an artwork that uses AI; it is a work that stages a conversation between a human sensibility and a machinic inner universe. The images do not behave like illustrations of an idea. They behave like signals from a submerged memory, fragments of a civilisation that never existed and yet feels weirdly remembered.

What moves me most is the sense that AI is being used here as a co-imagination rather than a shortcut. There is a humility and an audacity in letting a generative system push beyond what a single artist’s hand might invent. At its best, Remembering Orion feels like the machine is dreaming alongside the human, giving visual form to intuitions and myths that hover just beyond language. I find that deeply affecting: an echo of my own desire, as a viewer and writer, to think past the limits of the human without abandoning the human altogether.

Visually and conceptually, the project reads like speculative archaeology. Each image or sequence appears as a relic, a shard of some posthuman mythology pieced together from biotechnological futures and drowned pasts. I don’t experience these images as “content”; I experience them as artefacts. They invite me to interpret, to hypothesise, to build a culture around them in my mind in the same way I might when looking at a damaged fresco, an enigmatic votive object, or an orphaned film still.

Watching the videos unfold is like slowly unpeeling an artichoke. Each layer reveals a different emotional tone: at one moment ethereal, at another almost trolling, then suddenly unsettling, then unexpectedly devotional or tender. This constant modulation is part of the pleasure. The work never quite settles into beauty or ugliness, comfort or horror. Instead, the strange is liquefied, transformed into a flowing, unstable beauty that remains slightly out of phase with my expectations.

That instability is where the most powerful emotional moments occur. Sometimes the imagery feels almost horrible: hybrid bodies, uncanny rites, architectures that seem grown rather than built. But then, in the next beat, something in the composition, the colour, or the rhythm becomes tear-jerkingly glorious. It is as if the work allows horror and wonder to coexist in the same frame, and in that coexistence I glimpse a kind of posthuman sublime.

As an author and art historian, I am drawn to works that understand their own genealogies while also mutating them. Remembering Orion speaks fluently with the ghosts of early digital art, video installation, science-fiction cinema and symbolist painting, yet it does so through the nonhuman logic of a generative system. The result feels like an archive from an alternate future, assembled by a collaborator who doesn’t share my body, my memories or my time, but shares my hunger for images that think. That is why I love this artwork: because it doesn’t just show me another world, it expands the range of what my own imagination is capable of seeing.

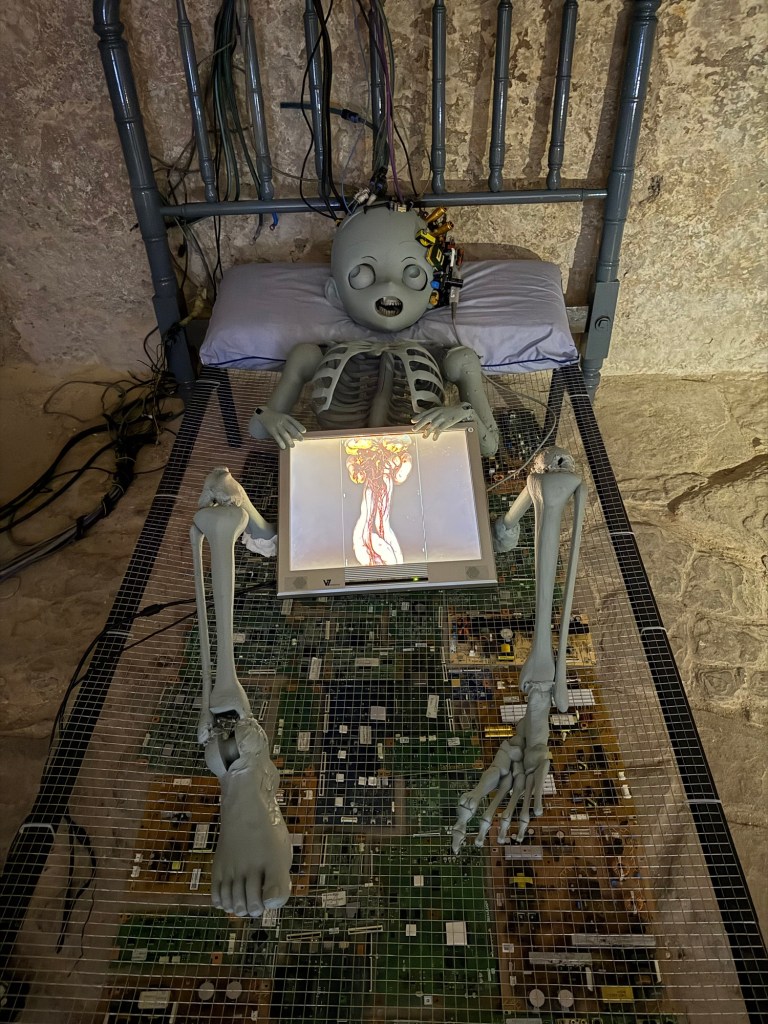

Solimán López

Manifesto Terrícola

Sinapsis

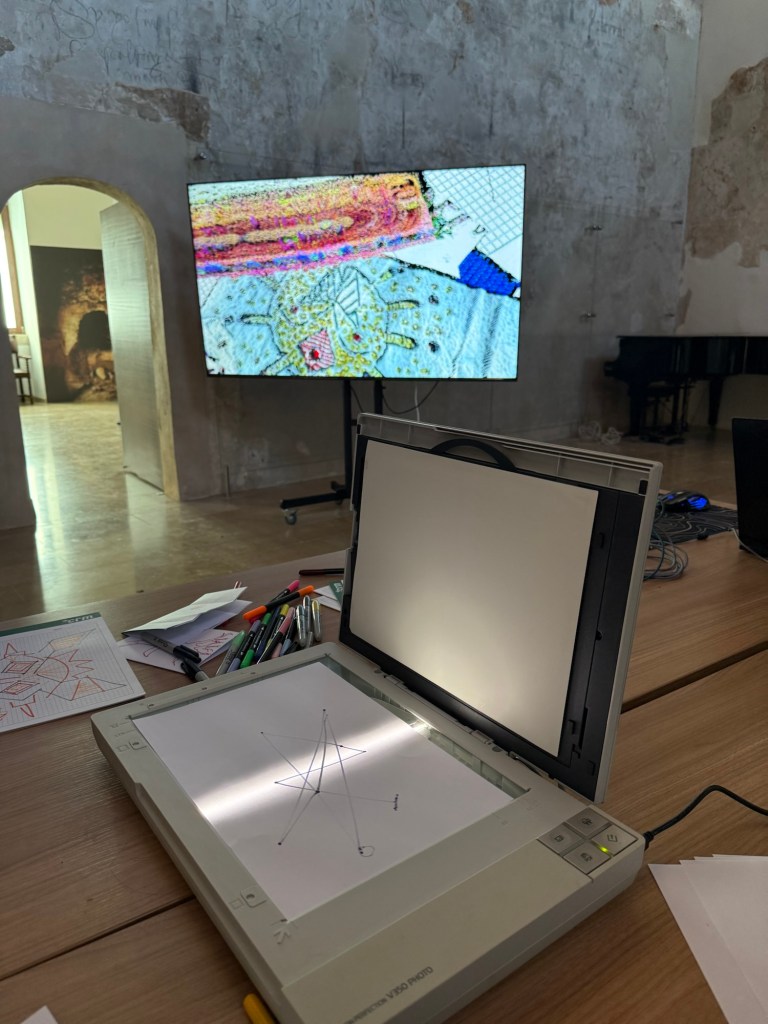

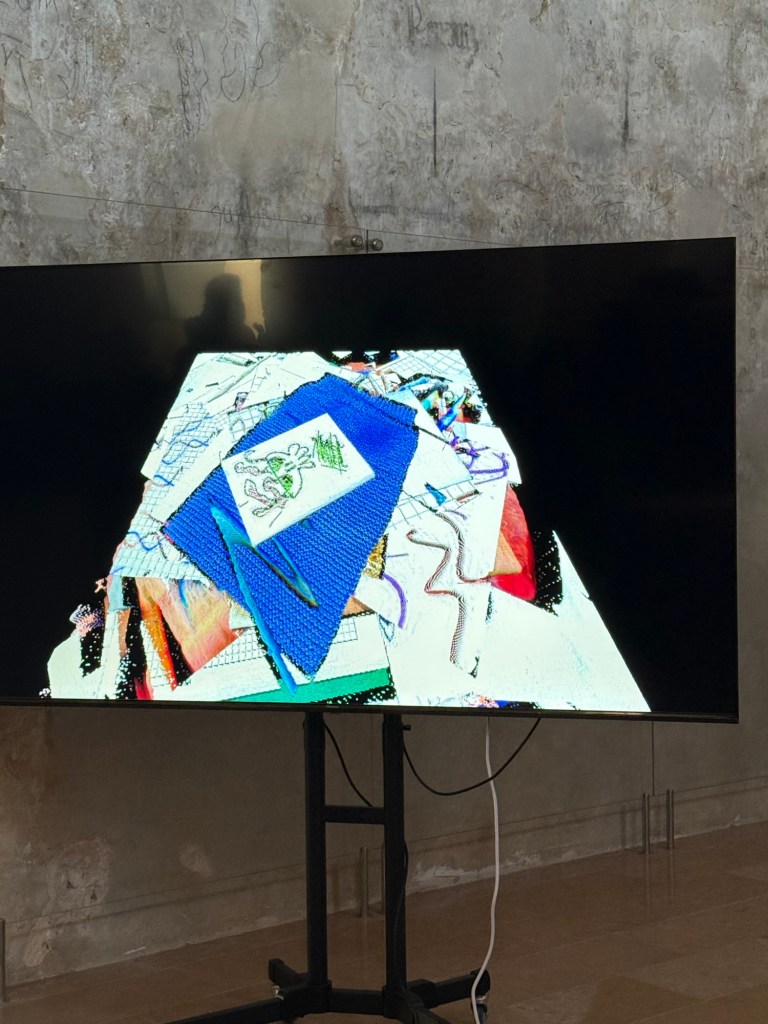

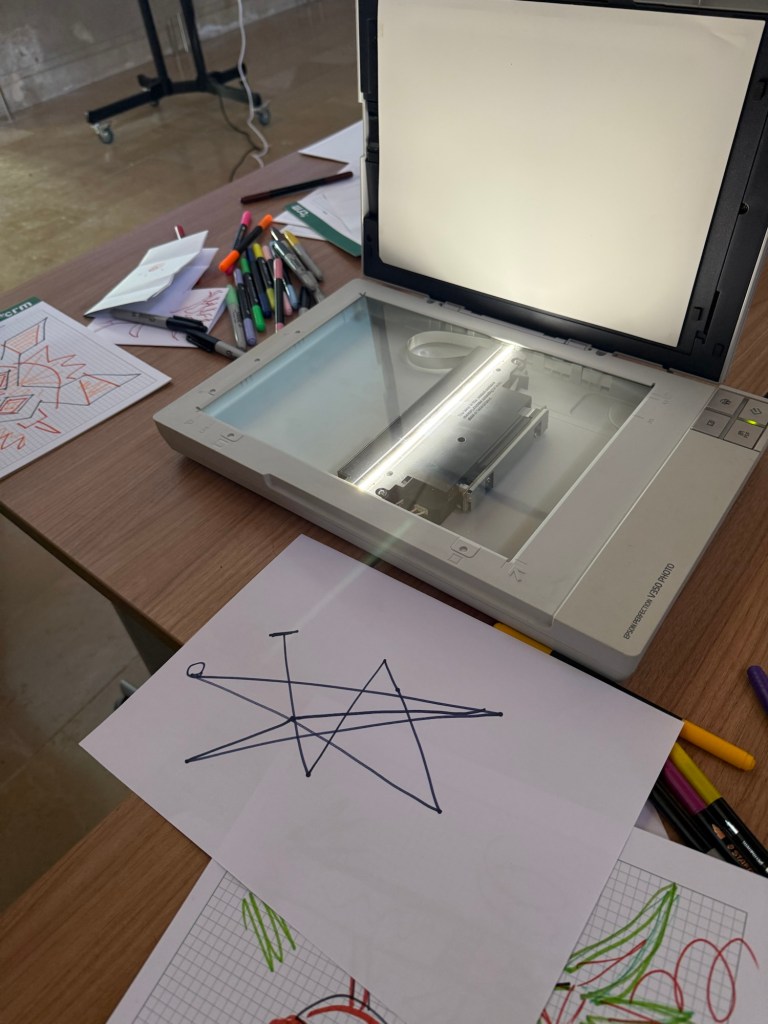

What we were invited to do is to create some kind of text or drawing or something on the paper and then put it into the scanner. The scanner would then scan whatever it was we put onto it and then incorporate that into what was going on with the screen which I’m assuming was plugging into the whole of the Internet and incorporating our input into it I’m not exactly sure how it worked. That’s why I really wanted to go back and talk to the people that were running it.. anyway when I did it, I incorporated the sigil that I’m working with at the moment.

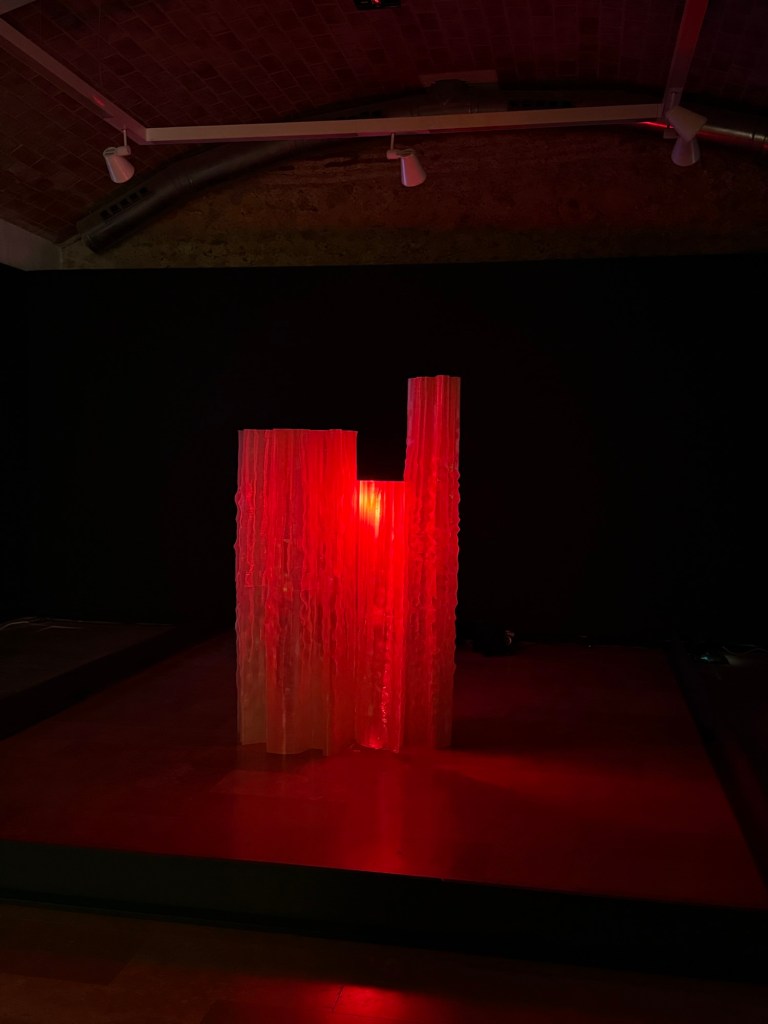

Post Natural Matter

JULIA MONGE

JOSÉ DEL REY ORTEGA

The kernel, chained

NICO GAY

JULIA MONGE

JOSÉ DEL REY ORTEGA

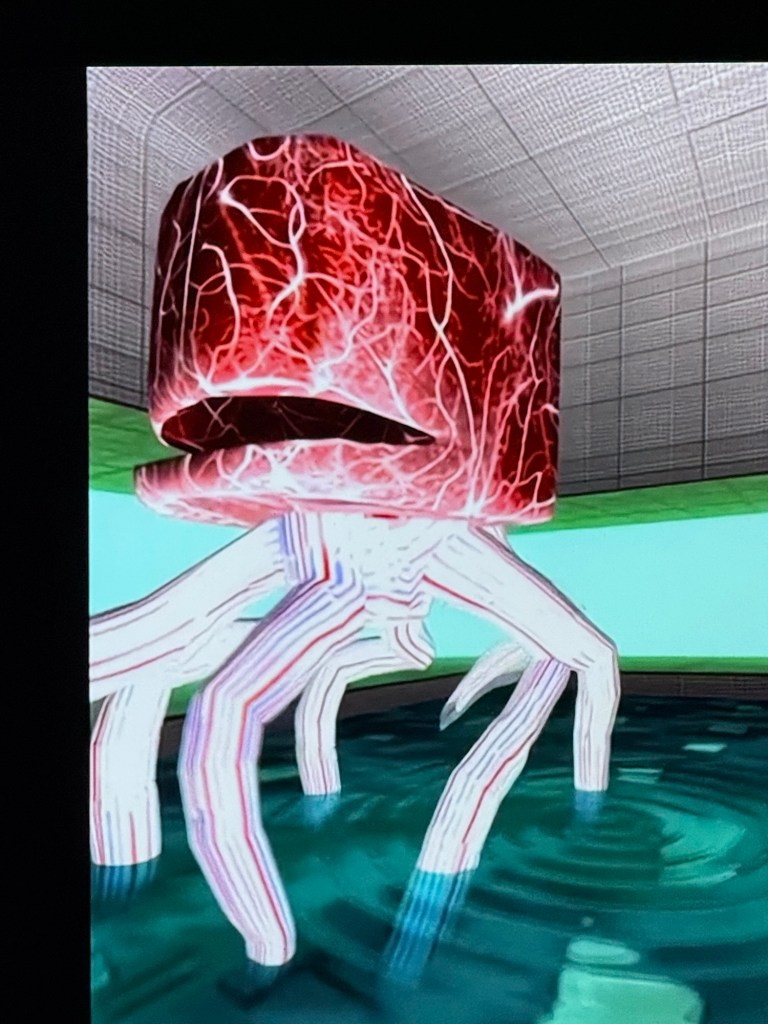

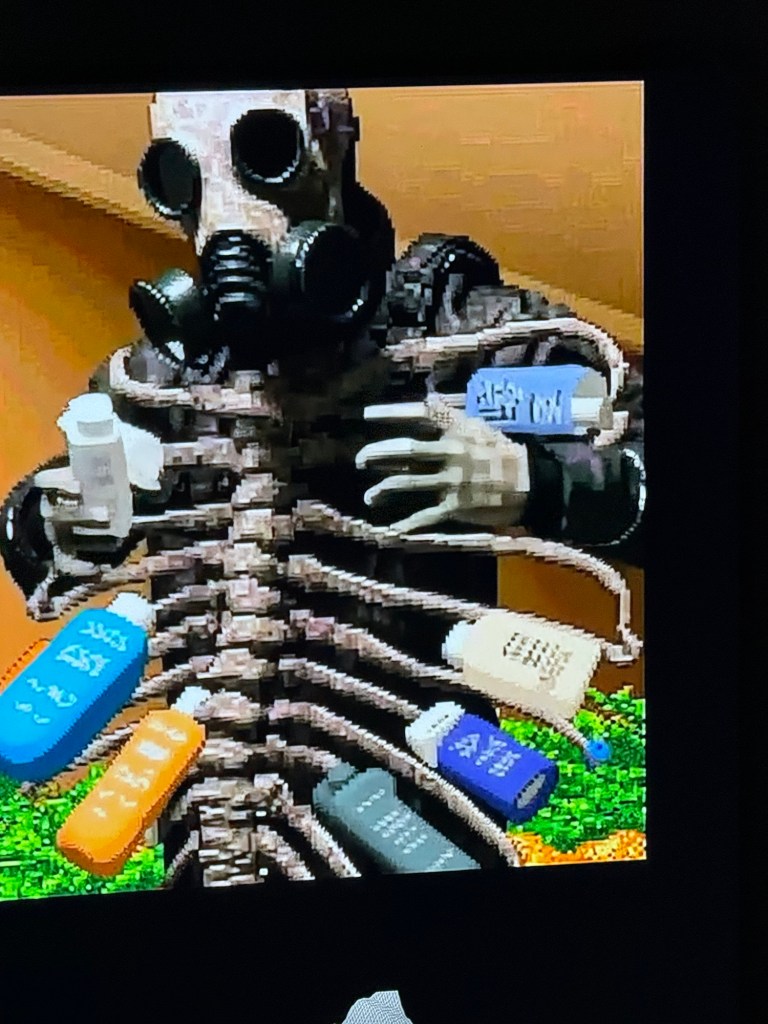

I was particularly entranced and spent a long time with this multiscreened piece called the chains of the kernel. Unfolding in time, each screen proffers a series of absolutely grotesque images that combine and recombine via algorithm processes into image sequences that are both highly disturbing and absolutely hilarious in the blackest humour. While not actually offensive, the images are extremely unsettling because we recognise them. We recognise them as part of the detritus of our culture; they’re like a monstrous ayahuasca encounter – but without the vomit. (I was immediately reminded of my last ayahuasca experience where I saw a lot of stuff exactly like this – it was extremely entertaining and cathartic.)

Well maybe that’s not really quite it because actually the screens themselves are on ayahuasca – they are vomiting up these horrific images at the same time. The images are creepy. They’re also hilarious. They appeal to the immature childish and quite shameful part of our ourselves – they are Shadow material part excellence. I love it and I remember myself saying while I was in the room that I really wanted to have the screens in my house so I could look at them all day long. What a strange confession! I guess it says something about me – but I bet I’m not alone.

But of course there was something more than self gratification in the plan of the project so I will let the artists themselves describe what it was all about: (rough translation from the Catalan)

“A kernel, in computing, is the center of the rules that keep the current system of making and using audiovisual content going. There is no interpretation or intention at this level, only operating conditions: input, process, output, repetition, optimisation, and continuity. The kernel can be seen in both humans and machines, and it is what makes the line between the two less clear.

Digital visual culture has been changing more and more to fit this model. The Internet is no longer a place to store and share data that represents the real world. Instead, it is a different dimension where the representation comes from the representation itself. Pictures that come from pictures; references that come from references. Production no longer relies on human physical experience and instead becomes contingent upon an uncontrollable generative inertia.

In this digital realm, AI does not create in a human manner; it merely hastens the recombination process without intent. When some of the material it is trained and consumed with is also synthetic, the system becomes recursive. It learns from its own results, makes its patterns stronger, and turns the leftover material into raw material.

In this cycle of creation and consumption, memes serve as basic units of thought devoid of contemplation. They are vectors of pure relationship within a latent collective space, where ideas, feelings, and gestures are rearranged without any order or direction. And this is how they make a language that is based on compressed associations, can be used again, and works with a culture that values repetition and quick recognition.

When production becomes automatic, whether by a person or an algorithm, sense is no longer needed. The kernel is still going and still chained”

Standing within the ancient Visigoth walls of Riba-roja de Túria, one cannot help but feel that time itself is being woven into new configurations. The dialogue between stone and circuit, memory and algorithm, transforms the castle into a living interface where history listens to the future. Int3raccion3s shows that art today is not about choosing between tradition and technology but about allowing them to coexist—to pulse together in the same space, to question and reimagine what creation means. In that sense, this exhibition is not simply a display but a meditation on how the human impulse to make, to connect, and to wonder continues across centuries and media alike.

You must be logged in to post a comment.